Here are our recommendations. A discussion follows.

- The GSEs should be preserved, mainly because they are the most effective institutions for providing liquidity to the mortgage market. Most mortgage investors, including depositories, prefer to hold liquid securities rather than illiquid whole loans. Wall Street securitization is not a substitute.

- Fannie and Freddie should be chartered as special-purpose banks, playing their historical roles of securitizing mortgages and holding some portfolio of loans. Their debt should be federally insured or guaranteed, as are the deposits of banks, and as with banks, the equity of the institutions should be the first backup to bondholders as the capital (or equity) of banks is the first backup to deposits. Their insured or guaranteed debt should not be counted as part of federal debt, as the insured deposits of banks are not. They should be subject to capital standards and supervision of their activities, and subject to restrictions on their activities, like banks. The capital standards, activity restrictions, and supervision need not be identical to those of banks.

- It is important to have two GSEs to assure competitive pricing of the guarantees on mortgages which go into MBS pools. Guarantee fees are not posted prices, but negotiated in secret. As a result, the pricing of guarantee fees is not collusive but close to perfect (Bertrand) competition with two GSEs. In the trade-off of standardization and homogeneity to promote liquidity (which calls for fewer GSEs) vs. competition to assure competitive pricing (which calls for more), two gets an excellent result, likely the best result.

- There are three choices for F&F ownership: 1) owned by the government, like FHA and Ginnie Mae; 2) owned as a cooperative, by member institutions, as both once were, and 3) owned by the general public. Fannie and Freddie should be owned by public shareholders, as banks are. We advocate ownership as public companies, but with explicit and priced federal backing, like banks.

Securitization is most efficiently done by institutions that isolate default risk and create homogeneous securities.

The most important reason to preserve the role of the GSEs is that they bring standardization and liquidity to the mortgage market, both in terms of the loans they securitize and in the structure of the mortgage-backed securities (MBSs) created from mortgages. This standardization makes their MBSs more liquid, and as a result of greater liquidity, more valuable. More valuable MBSs feed back to lower interest rates for mortgage borrowers. There are two features of GSE securitization that are valuable.

The very first effort at mortgage securitization was undertaken by Ginnie Mae, a 100% full-faith-and-credit government institution, designed by bureaucrats. This was part of the reorganization of Fannie Mae in 1968, done to get Fannie’s debt off the federal books. Ginnie Mae securitized already federally-insured mortgages made through FHA. The additional guarantee of timely payment of interest and principal from Ginnie Mae was a small extension of the federal backing. But the results were dramatic: the creation of Ginnie Mae lowered FHA borrowing rates by 60 to 80 basis points. With the real, long-term mortgage interest rates in the region of 4 to 5%, this was a large, not small, change. This seemingly small transformation of a federally-insured mortgage into a federally-insured liquid security made a big change in the cost of homeownership.

Evidently, all holders of mortgages, even the banks and thrifts who originated loans, preferred holding liquid, securitized mortgages over illiquid whole loans. Depositories (banks and thrifts with insured deposits) and other federally affiliated institutions (Freddie, Fannie, and the Federal Home Loan Bank) remain the largest investors in the outstanding MBSS created by Ginnie, Freddie, and Fannie today.

Ginnie Mae could only securitize loans insured by FHA or guaranteed by the Veterans Administration. So the thrifts quickly created Freddie Mac to securitize mortgages for the part of the market known as “conventional”, the slice larger than FHA will insure but smaller than “jumbo”. Freddie was up and running by 1970. Fannie began to securitize mortgages in the late 1970s.

Why is their approach to securitization so successful and why can’t Wall Street financial institutions duplicate it?

First, Freddie and Fannie isolate the default risk on their MBSs by guaranteeing them against default risk. Investors in F&F MBSs bear only the risk of changes in value coming from interest rate fluctuations, including prepayment risk. Risk from default losses remains with the shareholders of F&F. It is not the elimination of risk so much as the elimination of the need for continuous re-evaluation of risk on individual MBSs that is important. Guaranteeing the pool of loans against default relieves the security holders of the necessity of re-analyzing and re-valuing the default risk of the security. If security holders did have this burden, investors would put a lower value on the securities because of the cost of investigation necessary before undertaking an investment, and because different MBSs hold mortgages from different parts of the country, their default risk would vary from security to security. Isolating this ongoing re-valuation is efficient. Once the loans are made, they cannot be unmade, so time spent analyzing them only contributes to reckoning what today’s price should be, and cannot retroactively improve the allocation of capital.

Continuous analysis of the risk is necessary regarding the equity claims on F&F. Assigning the default losses to the single pool of equity claims in F&F is better than having the default losses fall on individual MBSs, which would vary in value depending on their different default rates.

When private entities such as individual banks or investment banks securitize mortgages, (all subprime MBSs were private-label securities, not Fannie or Freddie MBSs) they do two things differently. First, the default risk is borne within the MBS. The risk is generally not taken on by the issuer (as with Fannie and Freddie), or laid off to an insurer (as with FHA mortgages securitized into Ginnie Mae MBSs). Second, a private-label MBS is then divided into pieces or tranches depending on when and if principal payments are made. Some pieces have greater risk exposure to defaults by borrowers. Some pieces have more exposure to prepayment risk by borrowers. And some piece, however small, has a high probability of repayment and can thus be rated AAA. Because the pieces are not standardized, they cannot be as liquid.

The F&F default risk guarantees do for MBSs what insurance does for municipal bonds. Many municipalities are small, or obscure, and it would be a burden for the market to gather and process the information to keep up-to-date on them. To relieve the market of this burden, the municipalities who issue the bonds buy insurance against default. Their bonds are guaranteed against default by the insurer. Thus, the burden of investigating and monitoring lies with the insurance company, not the market. So long as the insurance company is solid (an issue in the recent crisis) the market can trade bonds of the same maturity but different locales as essentially identical.

A second feature of Fannie and Freddie’s MBSs is that they efficiently suppress information about the location of mortgages in individual MBS pools. Even with the guarantee against default, investors face another risk that varies slightly (much less than default risk) from one region to another: different speeds of loan prepayment. Some areas have higher turnover, and loans prepay when people move, and partly because from the point of view of an investor in an MBS with a default guarantee, a default looks like a prepayment: the investors gets her money back when the loan either prepays or defaults (with a guarantee.) So how do the GSEs keep the MBS market liquid despite some geographical differences in prepayment speeds? By not revealing the geography of loans in any given MBS. Wait! What about market transparency?

More transparency is not always better. This can be seen in another institution in the municipal bond market. A structure used for promoting liquidity in the municipal bond market is a random call feature used for bonds that fund small but long-lived projects. Take a dam, for example. Bondholders are repaid from citizens’ water bills. Such bonds are often structured in sets that repay at different times, for example, 10 years, 11 years, and so on up to 40 years. For little projects, each slice may be too small to find a liquid market. Instead, the entire issue is given the same maturity, but a specified fraction of it is called at random for repayment each year. The investors buy many such issues, and thus have a good idea of when they will be repaid, easily tolerate the uncertainty, and value the greater liquidity.

Suppose that right after the bonds were sold, the issuer spun the wheel to select the call date of each bond. Would it be efficient to release the information early, prior to the call? NO! Once the call dates were known, the bonds would degenerate into the tiny, illiquid serial bonds that the market was trying to avoid. What’s more, the issuer and the investors agree that the best arrangement is not to reveal early. This is a clear case where the optimal level of information is not the fullest.

In principle, the value of an MBS could be either increased or decreased revealing information that distinguishes them from one another. More pieces might accommodate a greater variety of investors with pieces precisely tailored to their risk tolerance. Or, it could be that liquidity concerns dominate, and that a larger, more homogeneous, more liquid market in MBSs tightens spreads and lowers prices. There are different ways of addressing risk, including pooling risk (MBSs vs. whole loans, even S&P500 futures vs. individual stocks in the S&P500) (see information theorist Hal Varian’s provocative ideas on subprime koolaid ), providing ratings (professional opinions on risk to make clear where similarities lie), and providing insurance (assignment of risk to a professional evaluator of risk for a fee). Each has its pros and cons.

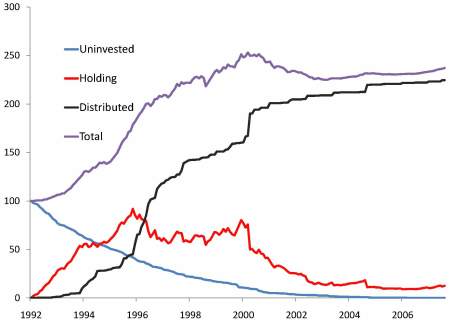

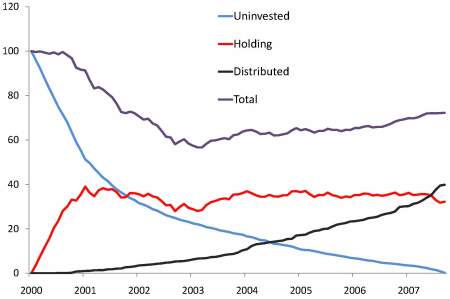

The experiment to show which is more important has been done: Some years ago Freddie Mac was persuaded to reveal more about the geography of its MBS pools on the theory that this would make the pricing more accurate. Since then, Fannie’s securities (MBSs) have consistently sold for a slightly higher price than Freddie’s because Freddie tells the market more about each one, and hence they are less like one another, and a bit less liquid. The Fannie MBSs are more alike because the market has no information with which to make distinctions among them. The really interesting thing is that the market prefers the security about which it is less informed. Over the period since 1998, the current coupon yield for Freddie MBSs has been above that for Fannie MBSs by on average 3 basis points, with a standard deviation of 1.5 basis points. From January 1998 to December 2008, the yield on the Freddie security was never below that on the Fannie security. And this is despite the feature that the Freddie securities pay the security holder slightly earlier, which in principle should make them more valuable. Yes, more transparency makes the securities of lower, not higher, value, on average.

So perhaps the Freddie securities are more accurately priced, but they are less valuable as a result.

By the way, the most complete federal guarantee does not necessarily imply that there is a substantial federal subsidy. FHA mortgage insurance has, through its history since 1934, covered costs through its insurance premiums (with periodic adjustments). The single-family part of Ginnie Mae has been a solid money-maker since inception.

The 30-year, fixed-rate, prepayable mortgage is unique and is not obviously viable without special federal support.

A large fraction of Fannie, Freddie, and Ginnie MBSs are still held by banks and thrifts with insured deposits, the Federal Home Loan Bank system, or by Fannie and Freddie themselves—in other words, under the federal umbrella. These MBSs contain almost exclusively 30-year, fixed-rate, prepayable mortgages.

The United States is unique in having a 30-year, fixed-rate, prepayble mortgage. Other industrialized countries have mortgages with long (25-30) lives, but only in the US do they have an interest rate that is fixed for the full term and the loan is prepayable. Only Denmark, population 6 million, has anything close. Other industrialized countries do have long-term (25 to 30 years) amortizing loans, but the rates adjust at least once every 5 years. As even we in the US have experienced, long-term, fixed-rate prepayable loans can cause systemic trouble.

The prevailing mortgage rate must anticipate the rate of inflation over the life of the loan. When the rate of inflation rises (as it did in the 1970s), loans become less valuable. Depositories who borrowed short (in the form of deposits) and leant long (in the form of mortgages) became insolvent when inflation rates and interest rates rose. By allowing federally-related institutions to make and hold mortgages of this design, we assign the systemic risk to taxpayers (who insure deposits explicitly, and stand behind Fannie and Freddie either implicitly or explicitly depending on your reading of current events). Given that nearly all income taxes are paid by homeowners, and that nearly all homeowners begin their home ownership with a mortgage, the beneficiaries of the system (homeowners, who are comforted by the fixed nominal payments) and the bearers of risk (the taxpayers) are ultimately the same folks. Only a country that was fairly optimistic about its ability to manage monetary policy would undertake such a program.

If the loans are at some times a problem, why not, like the other industrialized countries, allow only adjustable rate loans? Why bother to support the 30-year fixed-rate prepayable loan? Because the payment fixed in dollars comforts borrowers so much. This is evident first, from the observation that borrowers only choose ARM loans when interest rates are high and the term structure steep; when rates fall, all but the least-cash-constrained ARM borrowers refinance into fixed-rate loans. It is also evident in focus groups. Anyone who has observed focus groups discussing mortgage choice cannot but come away with a new appreciation for the security borrowers feel they get from loans with constant nominal dollar payments. Alan Greenspan may be right that this is an irrational, or silly, view, but as we saw when he suggested we do away with the 30-yr fixed-rate loan and make all mortgages adjustable-rate, the general public does not agree.

What about the portfolios?

F&F both have substantial portfolios of loans. Their portfolios are close to three-quarters of a trillion dollars each. We do not have a strong opinion on how large the F&F portfolios should be. But we do expect that any policy to whittle down the portfolios would only result largely in depositories holding more mortgages and MBSs than they now hold. In other words, the 30-year fixed-rate loans are not likely to leave the Federal umbrella, but only move to another place under it. Reducing the portfolios of F&F would not be without pain for the mortgage and housing markets. Even in the early 1990s, when the mortgages held by the insolvent thrifts had to find a new home, mortgages rates were clearly elevated by this displacement. We cannot imagine that policy makers would choose any time soon to force F&F to sell their portfolios, as this would just depress mortgage values and force already beleaguered banks to make down their assets once again. If the portfolios of F&F are to be whittled down, the least disruptive option may be to simply not have them buy any more loans for portfolio. As loans in the existing portfolios mature, the portfolios will shrink.

What about covered bonds?

Covered bonds have been promoted by some as superior to asset-backed securities. We see them as nearly identical, especially to Fannie and Freddie MBSs. Covered bonds are, like asset-backed securities, backed by the cash flows on a pool of assets, in the case of the mortgage market, a pool of mortgages. And covered bonds, like F&F MBSs, have more resources behind them than just the mortgages in their pools to cover losses. There are two differences between covered bonds and the MBSs issued by F&F, both essentially cosmetic. One is that the mortgages backing the bonds remain on the balance sheet of the issuer. Another is that the pool of assets backing the covered bond is usually larger in principal value than the bonds themselves, so that the security is over-collateralized. The MBSs issued by F&F are essentially also over-collateralized because they are guaranteed against default by F&F, but not by any explicit pool. If the default losses on a given pool were sufficiently large to invade the principal value of the pool, F&F are obliged to make up the difference from other assets. Thus, in essence, F&F MBSs are over-collateralized. So long as the securities outstanding as MBSs, and the experience on the mortgages behind them (in terms of defaults and prepayments) are well-disclosed, and the other assets are also fully disclosed, as those of F&F are, it should make no difference whether the securities are called covered bonds or MBSs or whether the recording of the securities is on the balance sheet or in some other part of their regular reports.

Private-issue MBSs are seldom over-collateralized. Instead, there is a single pool of loans, and it is securitized, usually with the default risk isolated in a particular part of the pool. If defaults exhaust the principal in this the high-risk part of the pool, then additional losses invade the other, higher-grade pieces. This happened with the securitized subprime loans. Anticipating that there was a large fraction of the principal value due on subprime loans that would surely be repaid, some pieces or tranches were rated AAA. As losses threatened to exceed the value of the pieces bearing the first losses, these additional losses threatened the higher-grade tranches, which caused them to be downgraded and to fall in value. This decline in value was then marked-to-market on the balance sheets of institutions holding them, (both F&F and larger commercial banks and mortgage banks), and some were, as a result, insolvent. It appears that the banks that securitized the loans (Bear Stearns, Merrill Lynch, Lehman, Citigroup, Countrywide…) were holding the first-loss, riskiest pieces.

Organization and Charter

What about the conflict of private profits and public mission at F&F?

We do not see any more conflict in having Fannie and Freddie owned by public stock holders and operating with a federal guarantee than we see for banks and thrifts organized in the same way. It is true that part of why F&F are so successful at funneling capital to the housing market is that they had implicit, now explicit, federal backing. This is true of the entire banking system as well. Indeed, it appears that the 30-year fixed-rate prepayable mortgage loan is not sustainable in a free market, and that government support is necessary for its existence. The bulk of such mortgages have been held in institutions that are under the federal umbrella, either depositories, F&F, or the Federal Home Loan Banks, since they were created by FHA in 1934.

The continuous hostility of the Wall Street Journal and the American Enterprise Institute to Fannie and Freddie is somewhat baffling. They complain in particular that F&F operated with the presumption of federal backing but earn profits like private institutions. How is this so different from what insured depositories (banks and thrifts) do? The WSJ never complains about deposit insurance for banks.

The banks themselves are also not exempt. Ken Lewis, the head of Bank of America (an insured depository), said just a few months ago, in November 2008 at a gathering in Detroit:

…the financial crisis also exposed the inherent conflict in the structure of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The GSEs were asked to serve the interests of private shareholders while fulfilling a public mission, all with “implicit” backing of the government. …. Their move in recent years to purchase lower-credit quality loans helped to fuel that market. … It was heads, investors win… tails, the taxpayers lose. We don’t think that’s a sustainable model.

Was there no similar conflict at the Bank of America? We imagine he feels a bit foolish about these comments today, having resisted one capital infusion on the grounds that his bank did not need it, but now pleading for, and about to receive, another. But he should have felt foolish long before, even been inhibited from making such comments, given that he runs an institution that also operates with federal backing, and could leave the taxpayers with vast liabilities. Bank of America should have deposit insurance, but it should fess up to not being an entirely free-market entity.

Ownership Structure

Why not a coop? Time was when F&F were each organized as cooperatives, (though not at the same time, see the short history of F&F at the end of this discussion) owned by the lenders whom they served. In those times, the largest commercial bank in the US had less than one percent of bank assets. While US banking is still competitive today, it is more concentrated now, and a handful of banks now hold close to half of bank assets. The conflict between smaller banks and larger banks in how the GSEs should be run would be greater now than it was in their former co-op days. We believe there are good reasons not to allow the largest banks to run the GSEs to the disadvantage smaller banks. Smaller banks deserve an important place in our banking system. There is accumulating evidence that smaller depositories treat their customers in a less exploitive way than do newer and less regulated financial institutions. In particular, they are less inclined to exploit financial confusion on the part of borrowers. See Stango and Zinman, Buck and Pence, and Agarwal et al. on the mortgage counseling experiment in Illinois.

Why not a government program like FHA? FHA and Ginnie Mae are playing a large and important role right now, with a market share of originations in 2008 of 25 to 30%. For some years, FHA has operated at a disadvantage to the conventional market because of the rigidities inherent to being part of the bureaucracy. First, FHA originations are slower than originations through F&F. According to FHA’s January 15, 2009, report on recent originations, average processing time was 2.5 months, roughly 10 weeks, from application to closing, even though most transactions used streamlined systems. FHA was slower to create automated underwriting systems, introducing them only after Freddie and Fannie both had systems in place. Second, FHA is more vulnerable to exploitive policies on the part of lenders. Fannie and Freddie have more flexibility for thwarting and discouraging exploitation by lenders. F&F can also adjust its guarantee fees to reflect its experience with a given lender, while FHA insurance premiums are one-size-fits-all. There have been episodes of lender exploitation of FHA (seller “gifts” of downpayments to borrowers, implicitly raising the loan-to-value ratios and default rates) that required legislation to fix that would have been promptly corrected by internal policies at Freddie and Fannie.

Why two GSEs?

One might think that with only two organizations securitizing mortgages, we would see tacit collusion outcome such as we get when two gas stations are on opposite corners. If one station lowers its price, its rival across the street sees that change at least as soon as any customer. The rival can respond instantly. The first mover sells no more gas, he just sells the gas for less. Thus, there is no incentive to lower price when the rival sees the change at least as soon as the customers do.

Freddie and Fannie don’t post their guarantee fee. Each deal is negotiated, customized, and secret. The ultimate results are seen only in quarterly summaries of business activity. Thus, customers do know price before rivals do, and know much more about the details of each deal. Two GSEs thus reach an outcome close to competitive, but give the maximum benefit of standardization and size for liquidity.

In principle, the Federal Home Loan Bank system could have created a third securitizing GSE. It has not, despite some efforts in that direction. We imagine that the reason it has not is that there are some conflicts of interest among the members about how the entity should be structured, with larger institutions wanting more power than smaller ones. They have a collective action problem. They cannot create a facility only for some members, and have been unable to negotiate to create a facility appealing to all.

What should be different?

The new charters for Freddie and Fannie should 1) establish higher capital requirements for Fannie and Freddie, and 2) have different capital requirements for different lines of business, in particular higher-default risk business.

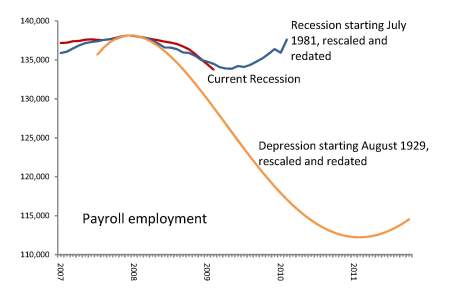

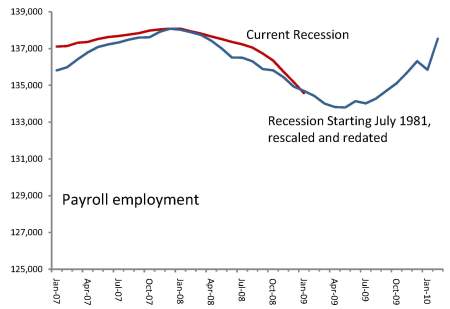

We won’t go on too long about this issue because we have already written about it earlier. We are not optimistic that we can alter asset markets to entirely avoid price bubbles (we seem to have had them from time to time as long as we have had asset markets, and they can be produced in experimental settings too), either in the stock market or the housing market. But if our financial institutions are less levered, the bursting of a price bubble is of less consequence. Given the big decline in house prices, it was inevitable that we would have a big decline in residential construction (the high prices resulted in over-building), which means a recession. Did the credit crisis make things worse? It is not yet clear how much the financial crisis and credit freeze added to this recession, but surely, it cannot have made it less severe.

Did Freddie and Fannie cause the subprime crisis?

The charters of the GSEs preclude them from securitizing subprime loans. Thus, they were unable to support subprime lending by any commitment to funding or securitizing them. They were followers, not leaders. When Fannie and Freddie did buy was some higher-rated pieces of subprime MBSs created by Wall Street. The ratings on these securities fell when the subprime loans began to default in large numbers. Freddie and Fannie also bought some Alt-A loans (these are loans to borrowers with good credit scores, but which are not as fully documented with respect to borrower income and assets as are prime loans) for their portfolios. They have lost money on these also. Despite their losses, their loss rate is less than one-third the loss rate of the 67 mortgage banks with assets of more than $10 bn.

We would hope that going forward, there would be more regulatory oversight of Fannie and Freddie, and that they would have higher capital standards. Of course these recommendations are not unique. Nearly everyone is calling for more oversight of any entity with any connection to mortgage lending.

How big a difference do Fannie and Freddie make?

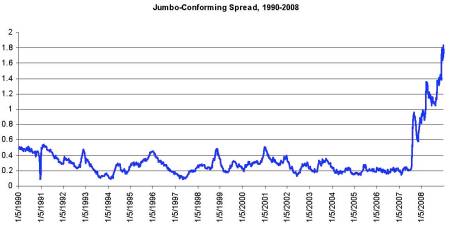

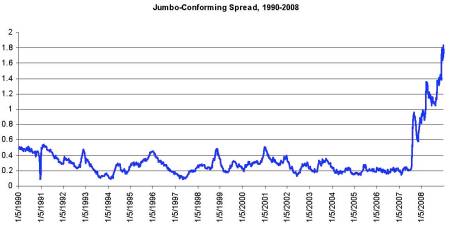

Most of the time, rates on mortgages that were eligible for purchase or securitization by Freddie or Fannie have been cheaper than larger, ineligible loans (“jumbo” loans) by 25 to 40 basis points. When the credit crisis began, one of the early manifestations of it was a great widening of the jumbo-conforming spread, out to 140 basis points (that’s 1.4 percentage points) and higher. The gap still stands at about 140 basis points.

A short history of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and the Federal Role in housing markets.

The 30-year, fixed-rate, prepayble amortizing mortgage was created by the FHA in 1934 as part of a program to revive the market for home loans: to encourage besieged banks to lend and wary consumers to borrow. Prior to the creation of FHA, loans for buying homes and farms had much shorter terms (three to ten years) and borrowers paid interest regularly, but the principal amount was all due at the maturity of the loan, as the principal on a bond is due upon the maturity of a bond. Homeowners either saved aggressively (creating their own sinking fund, in effect) as they were paying interest or planned on refinancing to a new loan when the term was up. We would now call this structure a balloon mortgage. So both the long term (30 years vs. three to ten) and the amortizing nature (paying both interest and principal each month) of the payment stream represented a new loan design.

Around this time Congress passed two other pieces of legislation regulating financial institutions, the Glass-Steagall Act and the McFadden Act. Together, they inhibited the movement of capital among banks and across State boundaries. The McFadden Act prohibited banks from having branches in more than one State. The Glass-Steagall Act prohibited banks from creating and selling securities. With nationwide branches, a bank could move capital from Idaho to North Carolina when more capital was demanded in North Carolina. If banks could have created and sold securities, they could have obtained new capital to lend by selling loans they had already made. Congress saw the difficulty created by Glass-Steagall and McFadden, and in 1938, established the Federal National Mortgage Association, FNMA, which came to be known as Fannie Mae, to compensate for the barriers to capital movement erected by Glass-Steagall and McFadden.

Fannie was originally organized as a cooperative. Banks that did business with Fannie (by selling loans to Fannie) also were investors in Fannie and provided Fannie’s capital in proportion to the amount of business done. Fannie grew slowly from 1938 until after WWII.

In the 1960s, there were many pressures on the federal budget, including the war in Viet Nam and the programs of the Great Society, and Fannie Mae’s debt, which was at that time counted as part of the federal debt, loomed. A federal budget task force was organized in 1968. One of its assignments was to get Fannie’s debt off the federal balance sheet.

This was done by two substantial re-arrangements. The first was to re-organize Fannie as a public corporation, with stock owned by the general public, not just by banks, and traded on the stock exchange. The corporation would issue bonds in its own name and use the proceeds to buy mortgages for its portfolio. Fannie would no longer be a bank co-operative.

The second was to take the FHA-insured loans (which represented an explicit Federal liability because of the full-faith-and-credit insurance) out of the Fannie Mae portfolio and pool them into mortgage-backed securities, then to sell these securities. A given security gave its holder the right to the payments of a specific set or pool of loans. The FHA insurance relieved the security holder of any risk coming from defaults by FHA borrowers. If borrowers prepaid, however, prepayments would flow straight through to security holders. Thus, if interest rates fell and homeowners refinanced at lower rates, Ginnie Mae security holders would get their principal back at a time when their reinvestment opportunity would be at a lower rate. On the other side, if interest rates rose, the likelihood of prepayment would fall, making it more likely that the loan would remain outstanding for its full 30-year term. This interest-rate risk, in which the investor loses due to prepayments if interest rates fall, and loses by virtue of a lower-valued loan if interest rates rise, is an important and defining feature of the 30-year, fixed-rate, prepayble mortgage loan. The risk for MBS holders was not different for the risk banks had always taken in making such mortgages, but it was a new feature for a liquid, traded security.

The securities created from FHA mortgages were then given a further guarantee of timely payment of interest and principal, through the newly created Government National Mortgage Association, known as Ginnie Mae. Ginnie Mae’s guarantee is a full faith and credit US federal guarantee. The additional burden to the federal government from this additional guarantee is de minimis, because the loans are already insured by FHA against loss of principal from default. Ginnie only has to pony up when a loan defaults, giving the security holder her principal back immediately, then waiting to collect the principal from FHA once foreclosure is complete. Ginnie gets 6 basis points of interest from the loan pool for this promise and has lost no money on the deal.

The success of Ginnie Mae was immediate and astounding. Within a year, it became clear that the creation of Ginnie Mae and its ability to turn illiquid, hard-to-evaluate, hard-to-sell, whole loans into liquid, easy-to-sell securities lowered interest rates on FHA loans by 60 to 80 basis points! Given that the real (inflation-adjusted) rate of interest on FHA mortgages had averaged around 4 to 4.5 percent, this was a big change, not a small one.

Ginnie Mae’s success made the thrifts (also known as Savings and Loan Associations, which have insured depositories, like banks) want a similar facility for loans larger than what FHA would insure. Within two years, by 1970, the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, which then governed the thrifts, had such an entity up and running in the Federal National Mortgage Corporation, now known as Freddie Mac.

Freddie was also operated as a cooperative. The thrifts (and banks) who did business with Freddie put up the money to provide its capital, and were in essence its owners (through their ownership in the district-level Federal Home Loan Banks, and these district banks held Freddie’s stock directly). Freddie’s activities were very different from those of Fannie. Fannie issued bonds and bought mortgages and held them. Freddie issued a few bonds, and used the money to buy mortgages, but then packaged the mortgages, attached its own guarantee against default risk, collected a little fee for this guarantee, (like FHA’s, but not explicitly federal), and sold the packaged loans as securities, much the same as Ginnie Mae did. Freddie’s primary activity was to securitize mortgages, not to hold them in portfolio. Freddie’s portfolio was essentially just a small liquidity facility until Freddie was privatized in 1989 as part of FIRREA.

Okay, now for a diversion into the thrift crisis. Be patient. In a page and a half we got from 1934 to 1980.

The rate of inflation had been rising through the 1960s, and by the 1970s it was up in double digits. The lenders who had made 30-year mortgage loans at 5 percent, 6 percent, and 7 percent were facing much higher rates than this to be paid for funds, and as a result, were insolvent. The value of their assets, the loans on their books, was lower than the value of their liabilities. The essence of their problem is that they borrowed short-term and invested long-term (in mortgages). If interest rates rose, what they had to pay for money also rose, but the rates they got on their old loans did not. The interest they received on their assets did not cover the interest they paid on their liabilities. The interest rate on one-month Treasury Bills reached a maximum of 21 percent in early (February) 1980.

The thrifts and Fannie Mae were essentially in the same tough place, seriously under water, on a market-value basis in 1980. The thrifts had assets with a market value of $700 billion, and liabilities of $800 billion. Fannie had assets with a market value of $70 billion, and liabilities worth $80 billion. But the deal between them and their guarantors (the federal government itself and insured federal depositories) was written in terms of book values, not market values, and there were no requirements to use mark-to-market accounting, so the institutions—banks and thrifts and Fannie—continued doing business while praying (along with a host of policy makers) for lower interest rates. The contrast between this insolvency, which was profound but not manifested in lender operations due to the prevailing accounting rules, and the current one, in which recognition of the insolvency has resulted in a full-blown credit crisis, is stark. We still speak of the “thrift crisis”, but the current financial crisis is much more crisis-full than was the thrift crisis. This does not necessarily mean the old way was better, but more on that later.

Note that as of 1980, when interest rates were at their peak, Freddie was entirely solvent. By virtue of only securitizing mortgages, and not holding and financing them in great volumes, Freddie faced no great interest rate risk.

So what happened in this great insolvency? Well, first we had a recession. Not because the thrifts were broke and wouldn’t make loans, but because the efforts that were made to bring the rate of inflation down first resulted in a sharp rise in short-term interest rates. The rise in interest rates starting in 1979 brought a decline in residential construction of more than 40% from 1979 to 1982, and then, as now, construction is a sufficiently large sector (about 5% of GDP) that when construction contracts by this amount, this contraction resounds around the entire economy. It was a very costly recession.

But the policies put in place to bring lower inflation succeeded, and in fits and starts, rates fell through the 1980s. Along the way some thrifts became insolvent on a book-value basis and had to be dissolved. More thrifts were insolvent on a market-value basis, and took extra risk because if they took risk and won, fine. If they took risk and lost, that was fine too, because they were in the hole anyway and the new risk was taken with Other People’s Money (mainly the taxpayers’). The obvious strategy for an insolvent thrift was to take some risk and try to get out of the hole. In 1989 Congress acknowledged this problem and provided the funds to close the remaining insolvent thrifts through the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act, FIRREA (pronounced Fie-REE-Ah). In the meanwhile, Fannie Mae had become solvent again from lower interest rates.

Once Freddie was privatized (also part of FIRREA), it immediately issued bonds on a great scale and accumulated a portfolio of mortgage loans. And as Freddie’s securitization program had been obviously successful, Fannie had begun securitizing loans also by the early 1980s. Thus, by the early 1990s, their structures and activities were essentially identical.

Okay, that’s the end of the history lesson.

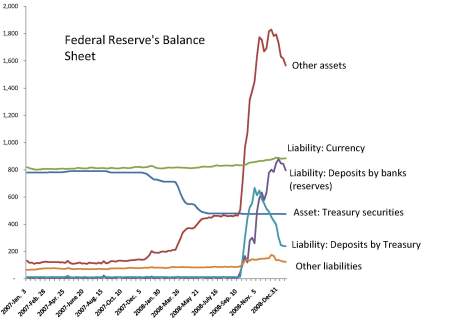

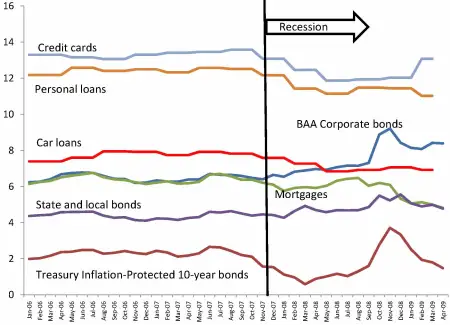

Rates paid by individuals–credit cards, pesonal loans, car loans, and mortgages–have fallen slightly, but by less than the decline in inflation, so the real rates are up a bit. Rates paid by corporations, measured here as BAA bond rates, have risen substantially in nominal terms and even more in real terms. Rates paid by state and local governments have also risen in slightly in nominal terms and more in real terms.

Rates paid by individuals–credit cards, pesonal loans, car loans, and mortgages–have fallen slightly, but by less than the decline in inflation, so the real rates are up a bit. Rates paid by corporations, measured here as BAA bond rates, have risen substantially in nominal terms and even more in real terms. Rates paid by state and local governments have also risen in slightly in nominal terms and more in real terms.

Posted by Woodward & Hall

Posted by Woodward & Hall